In 1921 Albert Wallace Hull invented the

magnetron as a powerful microwave tube.

Magnetrons function as self-excited microwave

oscillators. Crossed electron and magnetic fields are used in the magnetron

to produce the high-power output required in radar equipment. These

multicavity devices may be used in radar transmitters as either pulsed or cw

oscillators at frequencies ranging from approximately 600 to

30,000 megahertz. The relatively simple construction has the disadvantage,

that the Magnetron usually can work only on a constructively fixed

frequency.

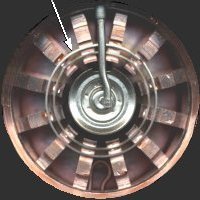

Physical construction of a magnetron

The magnetron is classed as a diode because

it has no grid. The anode of a magnetron is fabricated into a cylindrical

solid copper block. The cathode and filament are at the center of the tube

and are supported by the filament leads. The filament leads are large and

rigid enough to keep the cathode and filament structure fixed in position.

The cathode is indirectly heated and is constructed of a high-emission

material. The 8 up to 20 cylindrical holes around its circumference are

resonant cavities. The cavities control the output frequency. A narrow slot

runs from each cavity into the central portion of the tube dividing the

inner structure into as many segments as there are cavities.

| |

resonant cavities |

anode |

|

Figure 2: Magnetron МИ 29Г of the Bar Lock |

| filament leads |

|

cathode

pickup loop |

| Figure 1: Cutaway view of a magnetron |

The open space between the plate and the

cathode is called the interaction space. In this space the electric and

magnetic fields interact to exert force upon the electrons. The magnetic

field is usually provided by a strong, permanent magnet mounted around the

magnetron so that the magnetic field is parallel with the axis of the

cathode.

Figure 3: forms of the plate of magnetrons |

|

The form of the cavities varies, shown in the

Figure 3. The output lead is usually a probe or loop extending into

one of the tuned cavities and coupled into a waveguide or coaxial

line. |

a) slot- type

b) vane- type

c) rising sun- type

d) hole-and-slot- type |

Basic Magnetron Operation

As when all velocity-modulated tubes the

electronic events at the production microwave frequencies at a Magnetron can

be subdivided into four phases too:

- phase: Production and acceleration of an electron beam

- phase: Velocity-modulation of the electron beam

- phase: Forming of a �Space-Charge Wheel�

- phase: Giving up energy to the ac field

Figure 4: the electron path under the influence of the

varying magnetic field. |

|

1. Phase Production and acceleration of an

electron beam

When no magnetic field exists, heating the cathode

results in a uniform and direct movement of the field from the

cathode to the plate (the blue path in figure 4). The permanent

magnetic field bends the electron path. If the electron flow reaches

the plate, so a large amount of plate current is flowing. If the

strength of the magnetic field is increased, the path of the

electron will have a sharper bend. Likewise, if the velocity of the

electron increases, the field around it increases and the path will

bend more sharply. However, when the critical field value is

reached, as shown in the figure as a red path, the electrons are

deflected away from the plate and the plate current then drops

quickly to a very small value. When the field strength is made still

greater, the plate current drops to zero.

When the magnetron is adjusted to the cutoff, or critical value

of the plate current, and the electrons just fail to reach the plate

in their circular motion, it can produce oscillations at microwave

frequencies. |

2. Phase: velocity-modulation of the electron beam

The electric field in the magnetron

oscillator is a product of ac and dc fields. The dc field extends radially

from adjacent anode segments to the cathode. The ac fields, extending

between adjacent segments, are shown at an instant of maximum magnitude of

one alternation of the rf oscillations occurring in the cavities.

Figure 5: The high-frequency electrical field |

|

In the figure 5 is shown only the assumed

high-frequency electrical ac field. This ac field work in addition

to the to the permanently available dc field. The ac field of each

individual cavity increases or decreases the dc field like shown in

the figure.

Well, the electrons which fly toward the anode

segments loaded at the moment more positively are accelerated in

addition. These get a higher tangential speed. On the other hand the

electrons which fly toward the segments loaded at the moment more

negatively are slow down. These get consequently a smaller

tangential speed. |

3. Phase: Forming of a �Space-Charge Wheel�

On reason the different speeds of the

electron groups a velocity modulation appears therefore.

Figure 6: Rotating space-charge

wheel in an eight-cavity magnetron |

|

The cumulative action of many electrons returning

to the cathode while others are moving toward the anode forms a

pattern resembling the moving spokes of a wheel known as a

�Space-Charge Wheel�, as indicated in figure 6. The space-charge

wheel rotates about the cathode at an angular velocity of 2 poles

(anode segments) per cycle of the ac field. This phase relationship

enables the concentration of electrons to continuously deliver

energy to sustain the rf oscillations.

One of the spokes just is

near an anode segment which is loaded a little more negatively. The

electrons are slowed down and pass her energy on to the ac field.

This state isn't static, because both the ac- field and the wire

wheel permanently circulate. The tangential speed of the electron

spokes and the cycle speed of the wave must be brought in agreement

so.

|

4. Phase: Giving up energy to the ac field

Figure 7: Path of an electron |

|

Recall that an electron moving against an E field

is accelerated by the field and takes energy from the field. Also,

an electron gives up energy to a field and slows down if it is

moving in the same direction as the field (positive to negative).

The electron gives up energy to each cavity as it passes and

eventually reaches the anode when its energy is expended. Thus, the

electron has helped sustain oscillations because it has taken energy

from the dc field and given it to the ac field. This electron

describes the path shown in figure 7 over a longer time period

looked. By the multiple breaking of the electron the energy of the

electron is used optimally. The effectiveness reaches values up to

80%. |

Modes of Oscillation

The operation frequency depends on the

measurements of the cavities and the interaction space between anode and

cathode. But the single cavities are coupled over the interaction space with

each other. Therefore several resonant frequencies exist for the complete

system. Two of the four possible waveforms of a magnetron with 8 cavities

are in the figure 8 represented. Several other modes of oscillation are

possible (3/4π, 1/2π, 1/4π), but a magnetron operating

in the π mode has greater power and output and is the most commonly

used.

|

|

Strapping

Figure 9: cutaway view of a magnetron, showing the

strapping rings and the slots.

Figure 8: Waveforms of the magnetron

(Anode segments are represented �unwound�) |

So that a stable operational condition adapts

in the optimal pi mode, two constructive measures are possible:

- Strapping rings:

The frequency of the π mode is separated from the frequency of

the other modes by strapping to ensure that the alternate segments have

identical polarities. For the pi mode, all parts of each strapping ring

are at the same potential; but the two rings have alternately opposing

potentials. For other modes, however, a phase difference exists between

the successive segments connected to a given strapping ring which causes

current to flow in the straps.

- Use of cavities of different

resonance frequency

E.g. such a variant is the anode form �Rising Sun�.

Magnetron

coupling methods

Energy (rf) can be removed from a magnetron

by means of a coupling loop. At frequencies lower than 10,000 megahertz, the

coupling loop is made by bending the inner conductor of a coaxial line into

a loop. The loop is then soldered to the end of the outer conductor so that

it projects into the cavity, as shown in figure 1, view (A). Locating the

loop at the end of the cavity, as shown in view (B), causes the magnetron to

obtain sufficient pickup at higher frequencies.

Figure 10: Magnetron coupling, view (A) |

view (B) |

The segment-fed loop method is shown in view

(C) of figure 2. The loop intercepts the magnetic lines passing between

cavities. The strap-fed loop method (view (D), intercepts the energy between

the strap and the segment. On the output side, the coaxial line feeds

another coaxial line directly or feeds a waveguide through a choke joint.

The vacuum seal at the inner conductor helps to support the line. Aperture,

or slot, coupling is illustrated in view (E). Energy is coupled directly to

a waveguide through an iris.

Figure 11: Magnetron coupling, view (C) |

|

view (D) |

|

view (E) |

Magnetron tuning

A tunable magnetron permits the system to be

operated at a precise frequency anywhere within a band of frequencies, as

determined by magnetron characteristics. The resonant frequency of a

magnetron may be changed by varying the inductance or capacitance of the

resonant cavities.

Tuner frame

anode block |

|

Figure 12: Inductive magnetron tuning |

|

inductive

tuning

elements |

An example of a tunable magnetron is the

M5114B used by the ATC- Radar ASR-910. To reduce mutual

interferences, the ASR-910 can work on different assigned

frequencies. The frequency of the transmitter must be tunable therefore.

This magnetron is provided with a mechanism to adjust the Tx- frequency of

the ASR-910 exactly.

Figure 13: Magnetron M5114B of the ATC-radar ASR-910

Figure 13: Magnetron VMX1090 of the ATC-radar PAR-80 This magnetron is even equipped with the permanent magnets necessary for the

work.

![]()